-Lucienne Bloch

__1909-1999

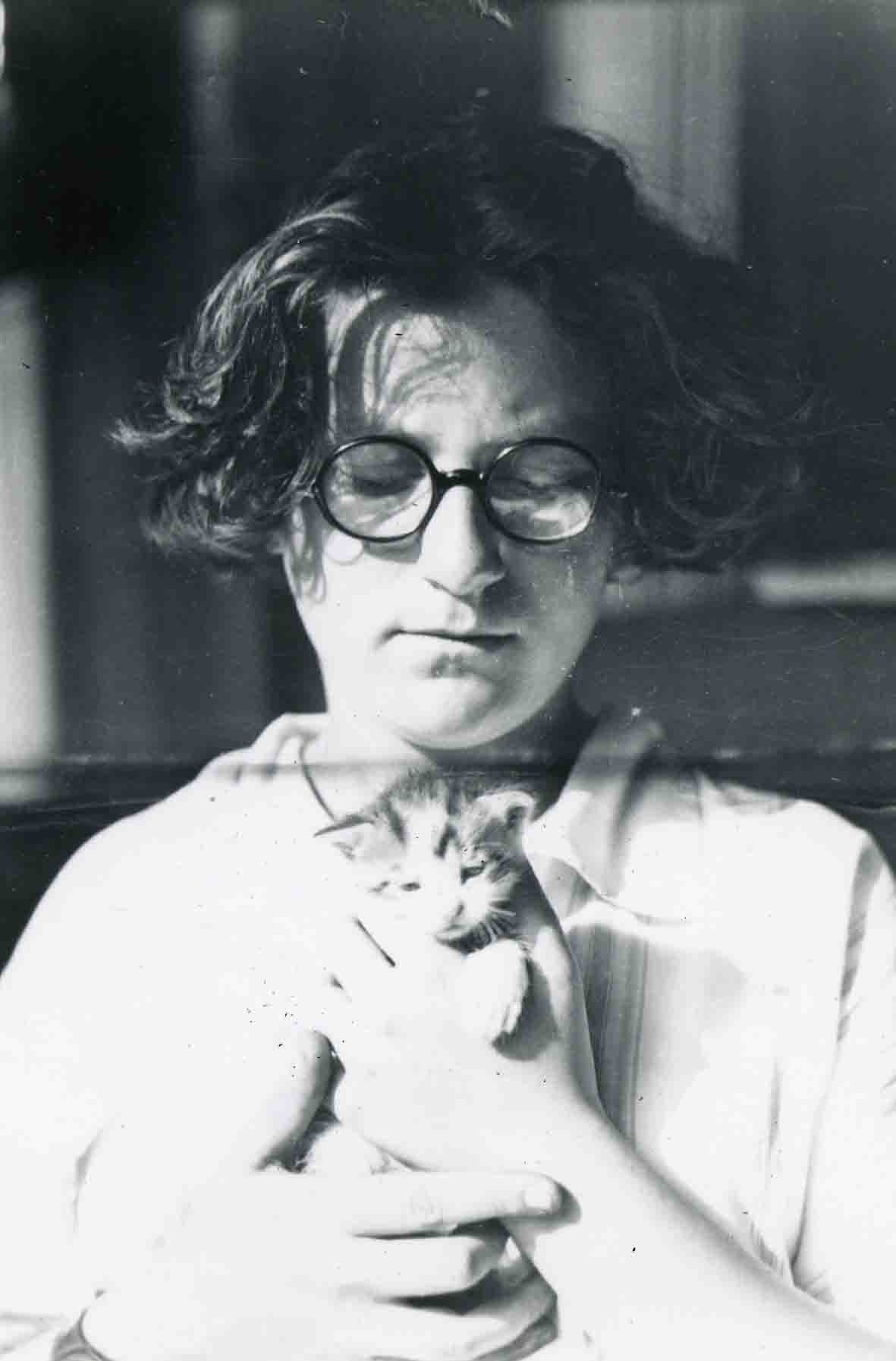

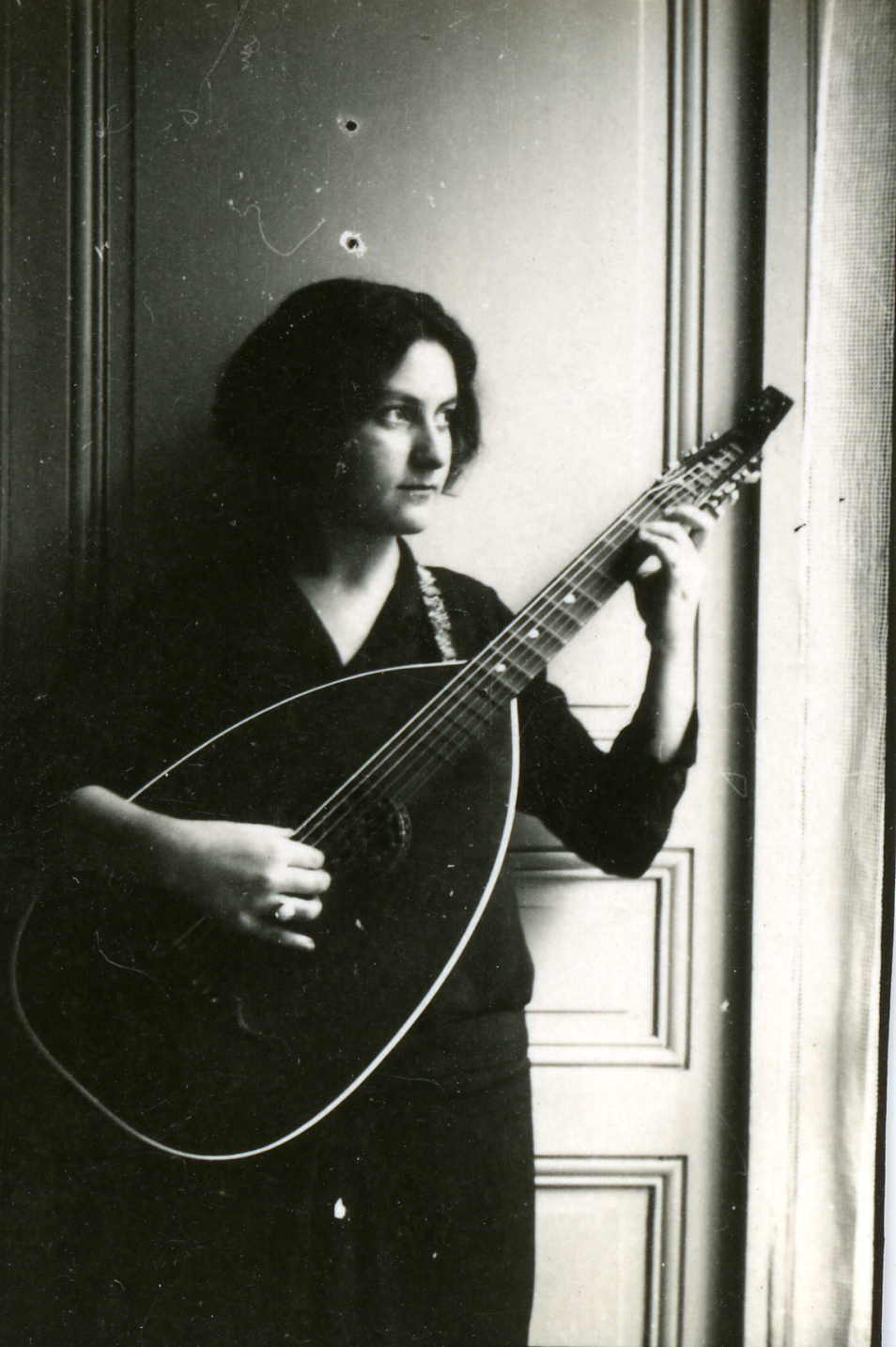

Lucienne Bloch was born on January 5, 1909 in Geneva, Switzerland. She was the third and last child born to international composer and photographer Ernest Bloch (1880-1959) and his wife, Marguerite Elisabeth Augustine Schneider Bloch (1881-1963), a musician as well. Lucienne was named after her godmother, the noted soprano, Lucienne Bréval.

Ernest saw that his children were allowed many opportunities for unique experiences in life and education. He sent his two daughters to piano lessons when they were quite young. Lucienne, an imaginative and artistic child, didn’t show much interest in the music lessons, so the young teacher gave her an edition of Lewis Carroll’s: Alice in Wonderland books, some watercolors and a brush. Lucienne’s first experience in art was filling in the pictures while listening to her sister take lessons.

1917 brought tensions of war and anti-Semitism throughout Europe so Ernest decided to move his family to America. Among the eclectic circle of friends that gathered for passionate and intellectual conversations, good food and drink, were other celebrated musicians, writers and artists of the time. The children were encouraged to participate whenever possible.

The Bloch children, Ivan (1905-1980), Suzanne (1907-2002), and Lucienne, received a vastly cultured upbringing. Many philosophical discussions were held around the dining table, which often included the pressing social issues of the times like racism, poverty, and class struggle.

Ernest sent his two daughters to learn the theory of music when Lucienne was 8 years old. Independent and true to her own feelings, she wrote on an empty page in the back of her music book “I’d rather do art!” When her sister saw this she brought it to their father. But, instead of becoming angry Ernest said to Lucienne, “Why didn’t you tell me?! There are enough musicians in the world! If art is what you want to do, go right ahead!” As a musician, composer, prolific photographer and fledgling artist himself, he knew the importance of engaging in what truly interested and inspired you. So he pulled down his collection of art books and said to his youngest, “Look, I have a library full of books; anytime you want to look at them, just take them.”

And so she poured over the volumes and learned about the different forms of art and the many artists who created it. From Gauguin to Michelangelo, Van Gogh to Da Vinci, Lucienne became inspired by the art that she saw. She was absolutely intrigued by the beauty of it all. This was just the beginning of a lifelong interest and desire to learn about every possible aspect of art. Her diverse artistic talents combined with a love for nature and the outdoors was the foundation for her artistically enriched life.

One of her first self-imposed projects, at the age of 11, was to write and illustrate her own children’s book entitled The Magic Rabbit. She even sent it to the Macmillan Publishing Company but they turned down her request to publish it. Lucienne was also eager to learn about photography from her father. Beginning at just 5 years old, Lucienne had assisted her father by standing in the sun exposing photographic paper under his negatives. When Lucienne was 12 years old her father gave her a Brownie Box Camera. Soon after she began making photographs with her father’s Stereoscope.

The Bloch family moved to Cleveland, Ohio in 1923 when Ernest was given the position of musical director at the newly established Cleveland Institute of Music. The following year Lucienne had her first artwork published. Her father had just finished composing Enfantines, 10 piano pieces for children. Lucienne made an illustration to go with each piece.

In Cleveland, Lucienne attended Hathaway Brown School for Girls. She excelled in the art courses they offered, but when it came time for Lucienne to begin high school, she yearned for a more artistically focused environment. So Ernest spoke to the director of The Cleveland Institute of Art and showed him some of Lucienne’s work. The director told Ernest that if Lucienne could pass the exams that were given to the other College Freshman entering that year she could enter as well. She passed all the exams, and began attending The Cleveland Institute of Art at the age of 15.

In a letter from the registrar at that time, Lucienne was described as “… one of our most talented students and a young woman of unusual ability for concentration and application.” Out of 100 students, Lucienne won the scholarship for the best work done that year.

The Cleveland Institute of Art is where Lucienne had her first true instruction in art and where the fundamentals in her artistic style developed. The classes were all rigidly planned. The students would learn one subject in the morning followed by another in the afternoon.

There was a Hungarian teacher that taught Art in Nature, a very strict teacher. One day when the students in his class were enlarging a shell onto a piece of paper he came over to Lucienne and saw her sketching the fine details of the shell. He yelled at her “You lie!” This was quite a shock for her to hear. He then asked her, “What do you see first when you look at the shell?” She answered, “The shape of it.” “So why don’t you draw the shape right away?” He answered back. “The first thing you see, you’ve got to draw that right away; then the details can follow.” Lucienne was definitely influenced by this teacher. Knowing that he was her toughest teacher, Lucienne was determined to work as hard as she could in this area of art. Art in nature played an intrinsic part in her artistic style for her entire life.

In 1925 Ernest was given the position of director at the newly founded Conservatory of Music in San Francisco. Wanting his daughters to experience all that they possibly could in their single life, he decided to send them to Paris along with their mother. Where Ernest was encouraging towards Lucienne and her talents, her mother, Marguerite, was the opposite. A pessimist to the extreme, and one who rarely praised, Lucienne would spend most of her young adult life trying to please her mother’s cynical ways.

Lucienne continued her studies in art and enrolled in the Ecole National et Superier des Beaux Arts. It was mostly Americans attending these classes in Paris, and Lucienne found herself often the only artist among them who spoke French and could understand what the instructors had to say. The instructors only came once a week to critique the young artists’ work. She wanted to garner whatever she could from these professionals but soon realized it wasn’t all that she had expected. So she sought out to attain an apprenticeship with an established artist if possible.

She first studied with the sculptor, Antoine Bourdelle (1861-1929). Most of the students in his class were working from casts and using a lot of measurements, but Lucienne, ambitious as ever, was working freestyle. Whether she was working in clay or stone, she worked without the help of any apparatus, having the opinion that it was closer to how her favorite sculptor, Michelangelo, would have worked. (She would be disappointed to later learn that Michelangelo hadn’t worked freely at all but from little models that he measured, and that his assistants had helped him.) When Bourdelle made his infrequent trips to the class to critique the work of the students, he would say to Lucienne ‘Bon courage!’ because nobody else in the class was doing this. His encouragement inspired her tremendously.

Lucienne’s repertoire of artistic talents was further developed when she began studying with the painter André Lhote (1885-1962). At first, the techniques he taught were difficult for her to attain. She didn’t like the results of the bright colors she was expected to use, so she muted and toned down the colors trying to get an effect that was more visually pleasing and acceptable to her. Each of her new experiences added to the unique abilities she sought to acquire.

The actual time spent with both instructors was extremely limited so Lucienne was eager to receive constructive criticism from the friends she made in Paris. The group of people she sought out was similar to those she was used to associating with while living with her father; artists, musicians, writers, and the like.

In 1927 Lucienne was invited to join a former student and friend of her fathers, Roger Sessions, and his family at their summer home in Florence, Italy. While she was there, she took some time to appreciate the local art and decided to visit some of the museums in the area. After walking into one she was amazed at how much art had been packed into the building. The walls were completely covered with paintings stacked upon paintings. All of a sudden she became dizzy and felt sick to her stomach. She left the museum and ran to the sanctuary of the church next door, the Church of San Marco, to recover.

When she felt better, she looked around her and was amazed at the beauty and simplicity of the fresco murals by Fra Angelico, adorning the walls. This was art, she thought. There was no confusion on the walls surrounding her. She felt at peace and inspired at the same time. This experience played a significant role in the direction of her aesthetic vision in her artwork.

While living in Paris, the versatile young artist experimented greatly with a wide variety of subject matter because she was eager to learn and also talented. She was never bored as she was always engaged in a number of projects. On one trip, in 1927, when her father came to visit, he bought her a 35mm Leica camera. This was an exceptional gift that impressed both father and daughter alike.

In 1928 Ernest received a stipend that enabled him and Marguerite to take up residence in Roveredo, Switzerland, where Ernest would compose Avodath Hakodesh, (The Sacred Service). Lucienne joined her parents there for about a year. Ernest’s quick wit and acute perceptions afforded Lucienne many opportunities to discuss with him how she felt about life and death. Ernest was an avid naturalist and philosopher, and sharing this with his youngest daughter was a favorite pastime. They loved to explore the mountainous regions together, often spending entire days hiking, hunting mushrooms, sketching, making watercolors, and taking photographs. The countless hours spent exploring her surroundings helped to hone Lucienne’s artistic skills in a realist-style of artistry, combining her love of nature and creative vision.

During one of his solo excursions, Ernest befriended a man on a train ride. The man was Mr. P.M. Cochius, the director of the Royal Leerdam Glass Factory in Holland. When Ernest mentioned that his youngest daughter was an ambitious and talented young artist, an invitation was arranged for her to come and stay with the Cochius family and try her hand at designing glass sculpture. This opportunity gave Lucienne a chance to prove to herself the aptitude she had for new and unknown forms of art.

In 1929, Lucienne embarked on the journey that would lead her to her first paying job. The Cochius family proved to be a warm and inviting family. They were Theosophists and Lucienne learned firsthand about reincarnation and the beliefs of Divine Wisdom. The two daughters of the three Cochius children, Crystal and Sita, were close in age with Lucienne. There was an immediate friendship forged among the three girls, and this strong bond remained for the rest of their lives.

While in Holland Lucienne continued to be active artistically, transcending the essence of her surroundings in different ways. Woodblock cuts, wooden sculptures, sketches, paintings and photographs kept her busy when she wasn’t working closely with the men in the large glass factory perfecting her designs for the ease of multiple reproductions.

Through the Royal Leerdam Glass Factory, Lucienne received an invitation from Frank Lloyd Wright to teach sculpture at his newly formed school and residence, Taliesin, in Spring Green, Wisconsin. This kind of acknowledgement of her talent as an artist by someone of such stature strengthened her confidence tremendously. Her return to New York City in 1931 was a momentous event.

Lucienne took many photographs of New York City. The scenes that were the most compelling to her were the ones that translated to her a sense of being. Her photographs illustrated human nature through an artist’s lens, as timeless aspects of reality were seen through the times at hand. The world around her was changing drastically, and her uncanny view of it originated from living in it as a participant and not just an observer.

Within a short time, she had her first solo exhibit of her glass works. The images were even displayed in the New York Times’ magazine section. It was a successful event, which helped elevate her reputation as a gifted artist of remarkable versatility.

During a banquet to honor a one-man show at The Museum of Modern Art, Lucienne met a man who would forever change her life. The great Mexican Muralist, Diego Rivera, was going to produce 7 Fresco panels for the new Museum of Modern Art exhibit. A close friend of the family was hosting the banquet and so Lucienne was seated next to Rivera because, like Rivera, she was an artist and, both were fluent in French. For most of the evening the two were deeply engaged in conversation. It seemed that everything she knew about Fresco, that ancient and forgotten tradition of art used in the 14th and 15th centuries by her favorite sculptor, Michelangelo and Da Vinci, was all wrong.

Here was a 20th Century artist, a great Mexican Muralist, who was creating Frescos in his own country. Now he was going to create Fresco murals in the United States, and she could possibly learn the technique. Lucienne was more than eager to become involved with this exciting new venture. To prove her knowledge of the antiquated Fresco technique she offered to grind Rivera’s colors. She secretly thought that the simple method of refining Fresco pigments by hand must have been improved by now. She was certain there must be a machine to accomplish the tedious grinding of pure earth pigments with a stone, now that they were in the 20th century! To her surprise, Rivera simply agreed and told her to show up at 8:00 am the next Monday.

Filled with excitement at this opportunity, Lucienne reached out to shake the hand of the wife of Diego Rivera, an intriguing young woman now standing in front of her. This beautiful and exotic woman had dark eyebrows that met in the middle ‘like a bird in flight’. She was colorfully dressed in traditional Mexican costume, and as Lucienne reached enthusiastically to greet the compelling stranger, she was greeted back with the words, “I hate you!”

Frida Kahlo had been watching her husband and Lucienne in deep conversation all evening. But instead of shying away from the complex stranger, Lucienne was more fascinated than ever. To have this woman, this stranger, say something so absolutely real and not give a damn about the consequences, was refreshing. Lucienne was becoming more and more appalled by the decadence of the rich in the face of poverty that the rest of society was living in.

Lucienne and Frida quickly engaged in an intimate friendship based on integrity and trust. They found in each other, an affinity to be on the side of honesty and the under-dog. While assisting Rivera, Lucienne watched the great artist at work. She was captivated by the way he painted Frescos. To see the difficult technique completed with such skill and mastery had a great impression on her.

When the time came for the Rivera’s to move to Detroit, Michigan, and begin the Industry Murals at the Detroit Art Institute, Frida made Lucienne promise to come stay with them on her way to visit Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin.

When she arrived in Detroit, Lucienne was given a hearty welcoming. Frida had settled into the role of wife and homemaker comfortably, but she hated America. She wasn’t doing any artwork and Diego asked Lucienne to inspire Frida and get her to paint again.

For Frida to have a successful day she needed everything to be laid out like she was at school. So the two young women created a little school in their apartment. Besides doing art together, Lucienne taught Frida English, and Frida taught Lucienne Spanish and how to cook tasty Mexican meals. When they kept busy at work everything was fine. They could both work intently on different art pieces and feel an immense sense of accomplishment at the end of the day.

Lucienne often assisted Diego on his massive murals at the Art Institute where she learned the entire Fresco process from beginning to end. It was an amazing lesson and she could hardly wait to try it herself one day. It was an excruciatingly difficult medium and she was always up for a challenge like this.

It was an eventful day when Frida found out that she was pregnant. Even though this was the happiest of all circumstances for Frida, there was a sad consequence that had to be discussed. The doctors didn’t want Frida to keep the baby because her own health was put at risk. Frida would hear nothing else about it. She was going to take care of herself and do whatever it took to take care of the baby.

One evening Lucienne was awakened by the worst cries of despair coming from Frida’s bedroom. She walked in to see Frida sitting in a pool of blood, her hair sopping wet, and tears streaming down her face. She was screaming out in agony. Diego looked at Lucienne and told her to call the doctor. The ambulance came and rushed Frida to the hospital. Frida lost the baby in a very painful miscarriage.

Lucienne helped Frida to recover from one of the worst times in her life. She urged Frida to begin to paint again. Frida worked on some small paintings, which Lucienne felt were truly extraordinary. She thought that Frida’s paintings were as great in their dimension as Diego’s murals were in theirs.

The two young women were encouraged by Diego to try their hands at lithography. There was a little Arts and Crafts Guild down the block that had all the materials they would need to get started. Through many trials and lots of errors they taught themselves the art of lithography.

Lucienne loved the feeling of running a wax crayon over the polished stones. Her first design was of a Detroit playground with children playing. Frida made a scene showing herself at Henry Ford Hospital in tears, hemorrhaging with her fetus and cells dividing.

In the beginning they were horribly disappointed at how much hard work was wasted as time after time their prints would not turn out as expected. When Diego came to see them he encouraged them with his stories of having to do his own work over and over.

Frida worked only on one image while Lucienne experimented with many different ideas. Frida was very impatient with the litho work. Lucienne eventually helped Frida with the printing of her litho and the prints came out very fine and lifted her spirits.

One day Frida received a telegram from Mexico explaining that her mother was very ill. Diego told Lucienne that she must accompany Frida to Mexico, and he would pay for it. This was to be quite an adventure for Lucienne.

While the two young women traveled, Lucienne was taking photographs with her Brownie camera because her Leica was back in New York being repaired. She enjoyed the new experience as much as possible, even though she spent most of her time alone. The scenery, culture, and people made a magnificent impression on her senses. She sought out to immerse herself in the music of the area and found herself open to an entirely different world.

The house that Frida’s mother and father lived in was particularly beautiful to Lucienne. The color of blue that it was painted was remarkable, and all the trim had been painted a bright pink, creating a contrast that she thought was incredible. She walked through the gardens with Frida’s father, Guillermo, and discussed photography in depth. Lucienne played chess with the older gentleman for hours before the family finally brought them the distressing news that Frida’s mother had passed away after many hours of operations. All those around openly displayed the immense grief they shared.

The time spent with Frida and Diego were crucial in helping Lucienne establish her own sense of artistic style. By showing her how daring they were by using the conflicts in their own lives to their best advantage they allowed her to believe that going against convention, as she had in the past, was an acceptable way of acting out life as a true artist. One of the most important things she learned from her time spent with Diego was to do as much research as possible on the subjects she would create in her artwork.

Between Lucienne and Frida there was a silent understanding; they were friends and artists, independent and strong, and they were continually unwilling to conform to the standards of the times they found themselves in.

Soon after returning to Detroit with Frida, Lucienne went to check out Frank Lloyd Wright’s new school. Taliesin was certainly as beautiful as she had imagined, but when she arrived, Lucienne mentioned to Mrs. Wright that she hadn’t decided if she was going to stay. Mrs. Wright became decidedly cold and told a young fellow to take Miss Bloch and her bags to the visitor’s area.

Diego had been against her decision to go to Wisconsin, but Lucienne owed it to her adventurous spirit to go and see what was available. She soon found out that it was not exactly what she had expected. To begin with, the school was still being “created”. The fledgling artists were all supposed to work on the grounds for most of their day and didn’t have time to do much artwork at all. Even though she could foresee how it could eventually become an idyllic life for a young artist on the cusp of his or her career, she wanted to do more… now. She wanted to continue to make a living on her own with her own art as her means of support.

In early 1933, Lucienne went back to New York where she continued to create art, honing her skills in photography, lithography, sculpture, watercolors and woodblock cuts. She had 7 of her woodcuts published in a book entitled Free Vistas put together by Oriole Press Publisher, Joseph Ishill.

But what she really wanted at this time was to be swept off her feet in love. She always dreamt she would be with an explorer someday, someone who would make her pulse race with anticipation. But neither of the two men with whom she had affairs even remotely fit her expectations.

An ‘old’ friend from Detroit, a fellow assistant of Rivera’s, soon sought her out. Arthur Niendorf had found out where she was in New York City and had come by with another assistant of Rivera’s in the hopes of borrowing some money. Niendorf introduced the other assistant as ‘Dimi’ and explained their dire situation.

The two assistants had been sent to New York to prepare the walls at the new Rockefeller Center Building, so that when Rivera had finished the mural in Detroit, he could come back to New York and start painting on the mural immediately. Rivera hadn’t paid them very much, if at all, so Niendorf went to the only person he knew in this great big city. Lucienne was reluctant to lend the boys any money, knowing it wasn’t a good idea to lend money to a friend, but when Niendorf told her they’d make her the chief photographer of the Rockefeller Center mural, she couldn’t refuse. She would later say it was the best twenty dollars she ever spent.

In a very short time Lucienne was wondering which of the two boys she’d fall for. There was Art, a southern gentleman, who spoke with a twang and was very mild mannered. He was an artist from Texas. And then there was Dimi. His full name was Stephen Pope Dimitroff, and he had come over from Bulgaria when he was 10. She took him to be about 28, and he spoke as if he was the master of love affairs. He was an artist, a musician, and wrote poetry. He wore a swell, little workers cap and made her feel like he knew a thing or two about a thing or two.

It was only when Lucienne and Dimi were sent on an errand to get some slaked lime for the mural that she learned the truth about this Esperanto Star. He wasn’t even 23 yet and still a virgin. Lucienne decided she needed to teach this chum a few things about women. When he played for her his mandolin, she saw through to his soul. And when he read her his poetry, she could sense he was a deep and caring, young man.

It wasn’t long before they were arm in arm everywhere they went. And before they knew it, Steve had moved in with Lucienne. They would be up all night working on the mural, plastering the walls for Rivera, and then they would go by White Castle for a meal at 5 in the morning, getting home just in time to sleep most of the day away. Together, they both learned the intricate ins and outs of creating a Fresco mural from beginning to end.

Lucienne realized that she had better get the photographs she wanted of the mural now because things were heating up with the Rockefeller family. Lenin’s portrait that Diego had painted on the wall was causing quite a ruckus. The newspapers were coming by and Lucienne had to sneak her camera in to record the last photographs of the mural before it was covered and eventually destroyed.

The times were dramatically intense, but Diego Rivera managed to inspire these two devoted artists to create Fresco murals themselves. The confidence that they could succeed in this light never wavered. Their first project was in a Settlement House located in the lower East Side of Manhattan. Lucienne had always documented her native surroundings so it was natural to show the scenes of everyday American Life.

Lucienne had wanted to sign up for the Works Progress Administration, but one had to sign what they called a ‘pauper’s oath’. Dimitroff absolutely refused to sign it, even though he was completely broke. The Federal Arts Project managers asked Lucienne how much money she had, and she told them the truth - $60. They weren’t going to let her sign up because of this, but she told them by the end of the next week she would have nothing. She had rent due and she needed to eat. She was accepted. Lucienne was a Fresco muralist for the Federal Arts Project of the Works Progress Administration from 1934 - 1939. On September 5, 1935, Lucienne Bloch and Stephen Pope Dimitroff were married.

This same year Lucienne completed the mural at the Women’s House of Detention for Women on the 12th floor recreation area. In a newspaper article it stated, “In their make-believe moments the children in the mural were adopted and named... Such response clearly reveals to what degree a mural can, aside from its artistic value, act as a healthy tonic on the lives of all of us.”

After the birth of their first son, in 1938, the family moved to Flint, Michigan, Stephen Dimitroff’s hometown. Lucienne taught art classes twice a week at the Flint institute of Arts, painted private portraits in egg tempera and had a small weekly column in the local newspaper. They proposed a Fresco mural for the dining room at General Motors, something in the style of Rivera. After they’d been in Flint for about 8 years, having had 2 more children, they decided they had done all they could in Flint, so they sold their house and everything in it, loaded their car up with their kids, tents and sleeping bags, and camped their way west.

They finally settled on a steep hill in Mill Valley, California, overlooking the San Francisco Bay and remained there for 15 years while their children attended school. They were just down the coast from her parents who had settled in Agate Beach, Oregon. Lucienne continued to teach different forms of art classes to students both young and old as well as produce private portraits. Although her portraits largely done in egg tempera were highly detailed and accurate, her 2- minute quick line sketches done at arts and crafts fairs showed how she could amazingly capture the likeness of someone through just a few simple lines.

Lucienne tried her hand at different styles of painting but tended to stay primarily with a realistic approach to her subject matter. Under “Pond Farm Workshops” in the late 1940’s, in Northern California’s Russian River area, Lucienne and Steve taught students Fresco painting by creating a mural on the outside wall of the new grade school in Guerneville, California. Unfortunately, this building along with the mural was demolished in 1996.

Lucienne Bloch and her husband, Stephen Pope Dimitroff, influenced many college students in the art of the true Fresco mural painting, which led directly to the preservation of this long-ago, forgotten art. Together, they learned first hand from the master muralist, Diego Rivera, the unforgiving media that demands great assurance and skill. They shared their experiences while giving their classes, which created an aura of oneness and family with the students.

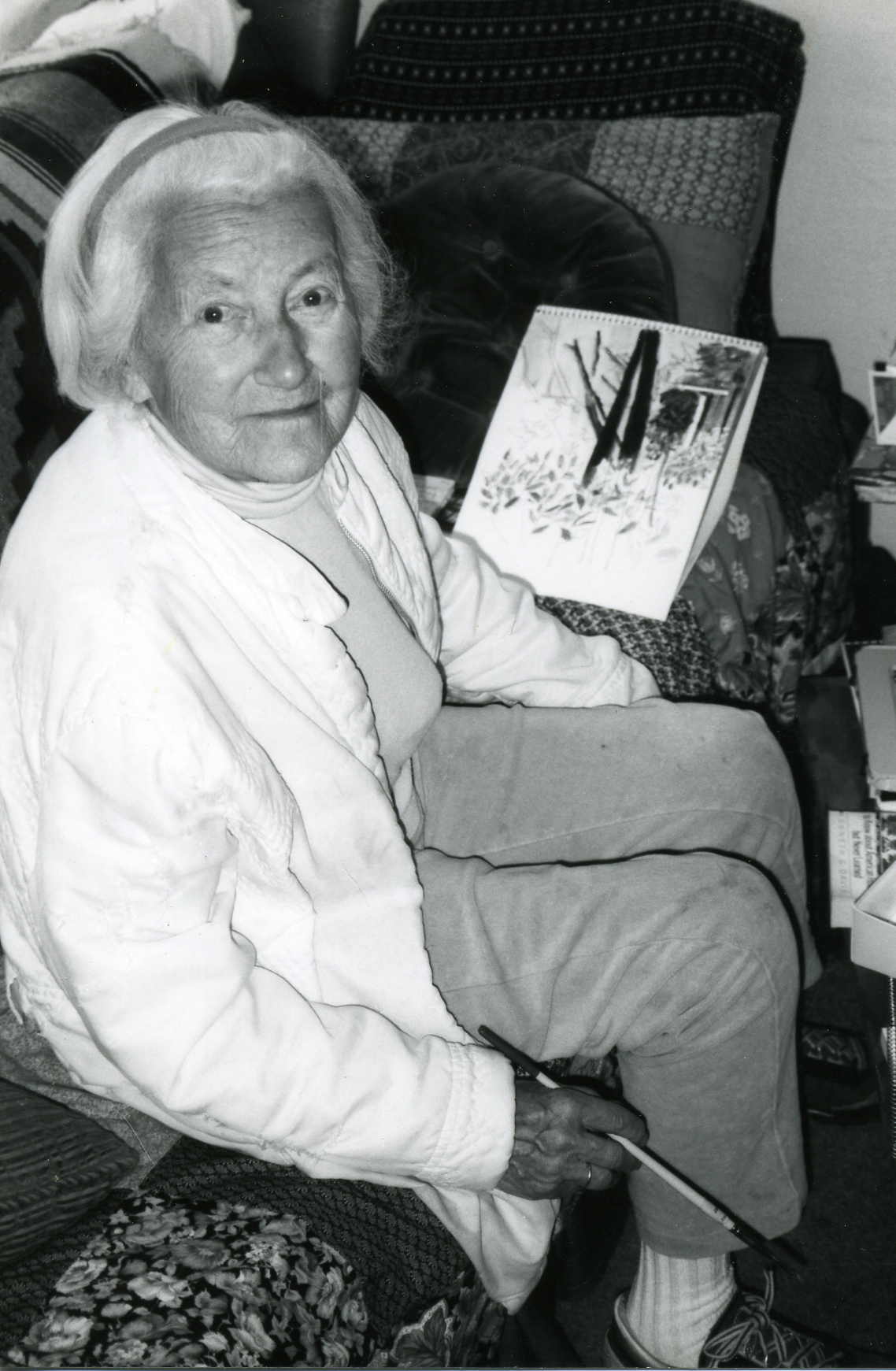

In the early 1960’s Lucienne and Steve moved to a small coastal town in Southern Mendocino County where they remained for the duration of their lives. They continued to teach Fresco workshops and mural commissions well into their 80’s. Their work was their joy. Since the day they met the two never stopped working together. Their great love, besides each other, was Fresco painting. Stephen Dimitroff passed away in their home in 1996. Two and one-half years later, at the age of 90, Lucienne Bloch also passed, in the same room as her husband.

Lucienne Bloch won many awards for the different types of art she created in her lifetime. Some were for her illustrations in children’s books, sculpture, silk screening, mosaics, as well as other mediums. Her works and writings have also been published many times.

The art world would change in many ways throughout the decades that Lucienne was artistically active. But she always remained true to her own values. It didn’t mater which fads were “en vogue”. It wasn’t important for her to follow in anyone’s footsteps. Lucienne Bloch created artwork for nearly a century executing literally thousands of pieces of multi-faceted art.

Because of her relationships with Diego and Frida, many scholars and artists sought her out to share her experiences with them. The details and accounts she gave, as well as her personal photographs of the times, have been invaluable to the art world.

Her family background and relations, coupled with the extraordinary times in which she lived, helped to foster her artistic visions….